Pavilion Tokyo 2020 Exhibitor Interview

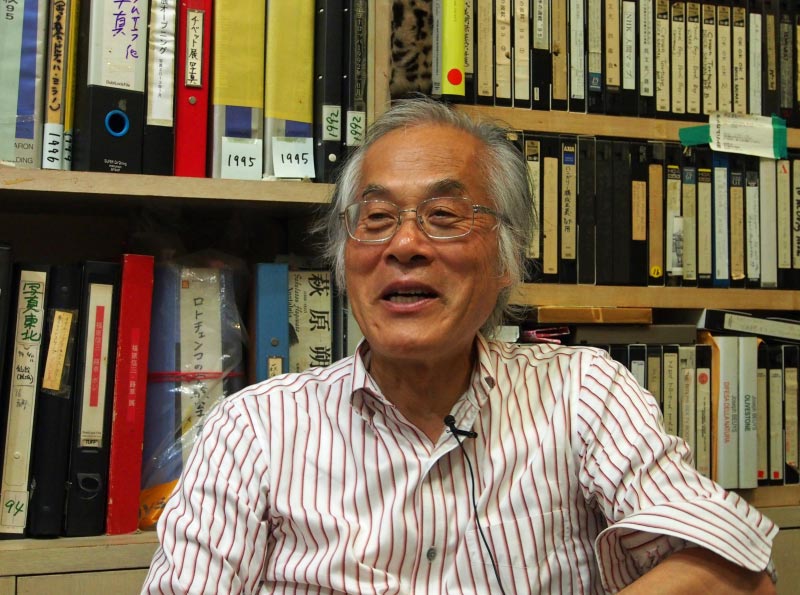

1.Interview with Architectural Historian and Architect Terunobu Fujimori (Part 1)

1.Interview with Architectural Historian and Architect Terunobu Fujimori (Part 1)

2019/12/6

【The 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics will open 6 months from now. Many official and unofficial cultural programs will be held concurrently with the Olympics. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government representing the host city of Tokyo and the Arts Council Tokyo at the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture are organizing a series of events called the Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL featuring the Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL Special 13 projects chosen out of 2,436 entries in an open RFP. One of the programs called Pavilion Tokyo 2020 will invite seven exhibitors who are internationally acclaimed Japanese architects and artists to build small temporary buildings within a 3-kilometer radius in the city of Tokyo.

The program was organized by the Executive Committee (Chairperson: Kengo Kuma) led by the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art. The Museum Director Etsuko Watari said, "We don't pay particular attention to artists' careers. We want to invite those who are willing to take up challenges and opportunities posed by the city of Tokyo using their unique approaches. Pavilions will be placed randomly over the city as if sprinkling hot sauce onto the pizza, and each exhibitor will express his/her thoughts on the city on Tokyo through his/her work. Interactions among them will surely bring interesting results." Pavilions are scheduled to be open to the public from June 6 to September 13, 2020.

On this occasion, we talked with architectural historian and architect Terunobu Fujimori (Professor Emeritus at the University of Tokyo) who has already developed ideas for the pavilion.】

The program was organized by the Executive Committee (Chairperson: Kengo Kuma) led by the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art. The Museum Director Etsuko Watari said, "We don't pay particular attention to artists' careers. We want to invite those who are willing to take up challenges and opportunities posed by the city of Tokyo using their unique approaches. Pavilions will be placed randomly over the city as if sprinkling hot sauce onto the pizza, and each exhibitor will express his/her thoughts on the city on Tokyo through his/her work. Interactions among them will surely bring interesting results." Pavilions are scheduled to be open to the public from June 6 to September 13, 2020.

On this occasion, we talked with architectural historian and architect Terunobu Fujimori (Professor Emeritus at the University of Tokyo) who has already developed ideas for the pavilion.】

―― What made you decide to take part in this program?

Fujimori:

They explained to me what the program was about and it sounded very interesting. Kengo Kuma is building the New National Stadium now. At the same time, some of the architects younger than Kuma are also getting worldwide attention. It would be very interesting to see small pavilions designed by young architects in the city of Tokyo. It is a common practice for art museums in Europe to commission architects to build small buildings, but that is not the case in Japan. It would be very interesting to do something like that in areas around the Olympic venues.

To be honest, I belong to a different generation. But considering the timing of my debut as an architect...

They explained to me what the program was about and it sounded very interesting. Kengo Kuma is building the New National Stadium now. At the same time, some of the architects younger than Kuma are also getting worldwide attention. It would be very interesting to see small pavilions designed by young architects in the city of Tokyo. It is a common practice for art museums in Europe to commission architects to build small buildings, but that is not the case in Japan. It would be very interesting to do something like that in areas around the Olympic venues.

To be honest, I belong to a different generation. But considering the timing of my debut as an architect...

―― You may be considered a young architect.

Fujimori:

I don't have the nerve to say so myself (laughs.) But my debut as an architect was around the same time or maybe later than Kuma's. (Fujimori's first work Jincho Kan Moriya Shiryokan was built in 1991.)

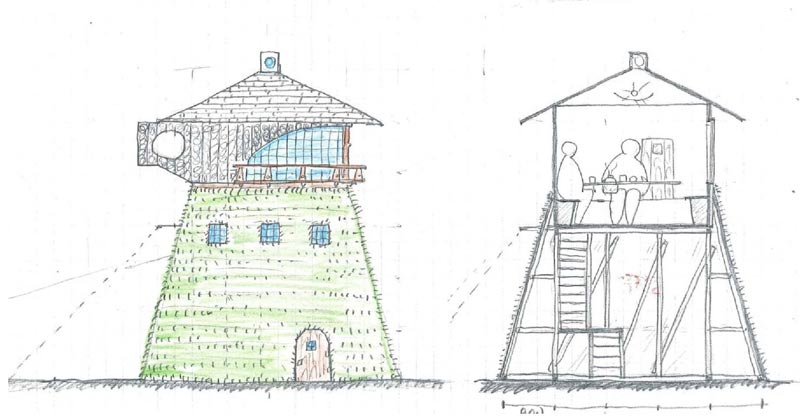

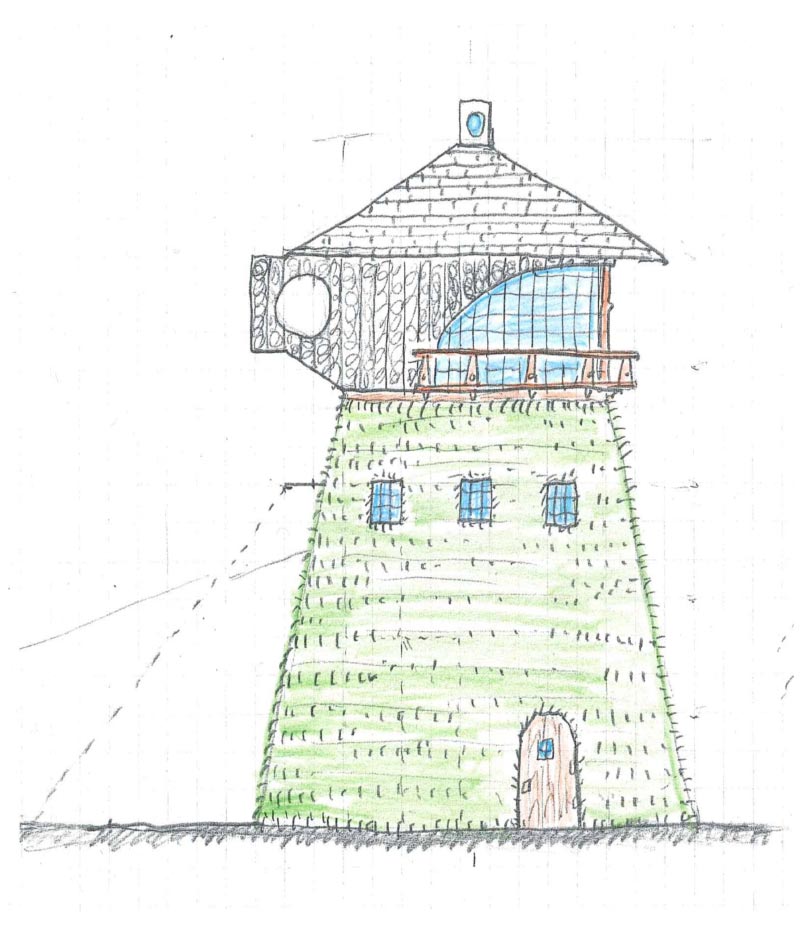

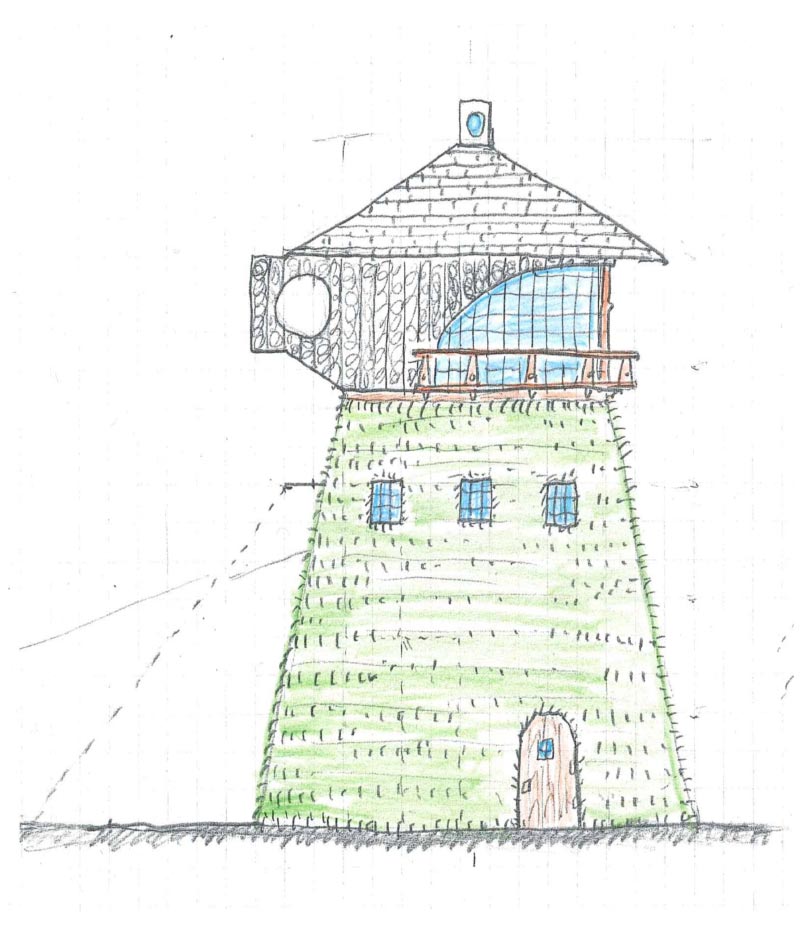

【Fujimori is planning to build a tea house like yagura (a raised wooden platform) or a gigantic lantern on the site overlooking the New National Stadium. A tea house made of burnt cedar will be raised three meters above the ground. Its "torso" will be covered with grass.】

I don't have the nerve to say so myself (laughs.) But my debut as an architect was around the same time or maybe later than Kuma's. (Fujimori's first work Jincho Kan Moriya Shiryokan was built in 1991.)

【Fujimori is planning to build a tea house like yagura (a raised wooden platform) or a gigantic lantern on the site overlooking the New National Stadium. A tea house made of burnt cedar will be raised three meters above the ground. Its "torso" will be covered with grass.】

―― Why do you want to build a tea house?

Fujimori:

Because I want to build a small building expressing Japan's omotenashi (Japanese hospitality) on the occasion of the Olympics. Tea houses built for clients are typical examples of omotenashi. The four-and-a-half-tatami mat size is a standard dimension of tea houses, but this time we are thinking of using a table and chairs, considering the comfort of guests from abroad. This tea house is built of burnt cedar and raised off the ground.

Because I want to build a small building expressing Japan's omotenashi (Japanese hospitality) on the occasion of the Olympics. Tea houses built for clients are typical examples of omotenashi. The four-and-a-half-tatami mat size is a standard dimension of tea houses, but this time we are thinking of using a table and chairs, considering the comfort of guests from abroad. This tea house is built of burnt cedar and raised off the ground.

―― Why do you want to raise it off the ground?

Fujimori:

Buildings raised high above the ground have been my favorite theme ever since I built "Takasugi An" in 2004. The tea house itself is clearly visible from all directions, and one has a good view of the stadium from there. A tea house should exert a sense of "otherworldliness." It would be better to raise it off the ground than to place it on the ground. One climbs up to the raised platform, goes up through a narrow and dark nijiriguchi (a crawl-in entrance), and discovers a scenery completely different from what he/she would see from the ground level. One can experience this kind of effect only in tea houses.

Buildings raised high above the ground have been my favorite theme ever since I built "Takasugi An" in 2004. The tea house itself is clearly visible from all directions, and one has a good view of the stadium from there. A tea house should exert a sense of "otherworldliness." It would be better to raise it off the ground than to place it on the ground. One climbs up to the raised platform, goes up through a narrow and dark nijiriguchi (a crawl-in entrance), and discovers a scenery completely different from what he/she would see from the ground level. One can experience this kind of effect only in tea houses.

―― How about the effect of framing the view with windows?

Fujimori:

Yes, the framing has a great effect. A scenery looks completely different when it is framed and seen from a slightly higher viewpoint than usual. And you have a full view of the stadium in front of your eyes.

Yes, the framing has a great effect. A scenery looks completely different when it is framed and seen from a slightly higher viewpoint than usual. And you have a full view of the stadium in front of your eyes.

―― The New National Stadium uses plenty of wood. Did you think about responding to the use of wood by building your teahouse using wood boards and grass?

Fujimori:

Not really. I had expected that Kuma's stadium would emphasize the materiality of wood more strongly, but it actually looks rather whitish and modern. It is well-designed, beyond my expectations. It perfectly embodies his concept of "architecture of defeat"–– by minimizing the visual impact. He knows how to "be defeated" in a perfect way.

Not really. I had expected that Kuma's stadium would emphasize the materiality of wood more strongly, but it actually looks rather whitish and modern. It is well-designed, beyond my expectations. It perfectly embodies his concept of "architecture of defeat"–– by minimizing the visual impact. He knows how to "be defeated" in a perfect way.

―― On the contrary, you are incorporating nature into your teahouse in a realistic way.

Fujimori:

That's right. We need to make an early start, because we are planning to grow grass from seed. A turf grass grower is doing experiments on the walls of my house (Tanpopo House) right now. They are using my house to grow grass and do experiments because tanpopo (dandelions) are currently not in season now.

The turfgrass grower specializes in lawns used in race tracks. Lawns on race tracks naturally peel off after the races, and they have to repair them in a week before the next races start. They say it is the most challenging part of their job.

That's right. We need to make an early start, because we are planning to grow grass from seed. A turf grass grower is doing experiments on the walls of my house (Tanpopo House) right now. They are using my house to grow grass and do experiments because tanpopo (dandelions) are currently not in season now.

The turfgrass grower specializes in lawns used in race tracks. Lawns on race tracks naturally peel off after the races, and they have to repair them in a week before the next races start. They say it is the most challenging part of their job.

―― Is this the first time for you to use grass specially grown for race tracks?

Fujimori:

Yes, it is the first time for me. According to their sales data, by the way, Kengo Kuma seems to be one of their largest purchasers. We are growing grass on the walls this time. According to the grower, we can even grow grass on overhangs. They are really fun to work with. They would call me up out of the blue and say, "Professor Fujimori, we are coming to Tokyo on business. Can we stay at your house?" They are a father-and-son duo from Shiga Prefecture and come to Tokyo in a truck they built themselves.

Yes, it is the first time for me. According to their sales data, by the way, Kengo Kuma seems to be one of their largest purchasers. We are growing grass on the walls this time. According to the grower, we can even grow grass on overhangs. They are really fun to work with. They would call me up out of the blue and say, "Professor Fujimori, we are coming to Tokyo on business. Can we stay at your house?" They are a father-and-son duo from Shiga Prefecture and come to Tokyo in a truck they built themselves.

"Tea House 2020" Elevation Sketch (Image courtesy of Arts Council Tokyo, Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture)

【One of the unique characteristics of Fujimori's architecture is that he chooses not to refer to specific architectural motifs from the past, even though he is an architectural historian. His architecture using simple materials including earth, stone, wood boards, plants among others evokes an image of primeval architecture which had existed before the history of architecture began, as well as a sense of "unbelongingness" to a particular country. Those who experience Fujimori's architecture feel a sense of nostalgia even though they have not seen it before.】

―― Is it going to be a building with a sense of unbelongingness to any particular country?

Fujimori:

Yes. The design of this building is going to be something that had never existed in the architectural history of any country, even though the tea room itself is based on Japanese traditions.

Yes. The design of this building is going to be something that had never existed in the architectural history of any country, even though the tea room itself is based on Japanese traditions.

―― As a Japanese architectural historian, maybe you could have chosen to show an authentic tea house like "Tai An" designed by Sen-no Rikyu (a national treasure in Kyoto.)

Fujimori:

Authentic tea houses are not so inspiring. There are so many authentic tea houses in Kyoto. Why do we have to show something like that now? There are many in Tokyo, too. Another thing, if we show overseas visitors an authentic tea house, they would probably feel, "Ah, this is Japan!" and just stop thinking further. I don't like that. It is like "Fujiyama, geisha"––the foreigners' stereotyped image of Japan. If that's what they want, we can simply show them the real Fujiyama and geisha to begin with. If we build a traditional tea house, something like that is most likely to happen.

Authentic tea houses are not so inspiring. There are so many authentic tea houses in Kyoto. Why do we have to show something like that now? There are many in Tokyo, too. Another thing, if we show overseas visitors an authentic tea house, they would probably feel, "Ah, this is Japan!" and just stop thinking further. I don't like that. It is like "Fujiyama, geisha"––the foreigners' stereotyped image of Japan. If that's what they want, we can simply show them the real Fujiyama and geisha to begin with. If we build a traditional tea house, something like that is most likely to happen.

―― Do you want to show them contemporary Japanese culture rather than traditional Japanese culture?

Fujimori:

That's right. I think it is the most important thing to do. I don't use shoji (paper screen) and bamboo because they evoke the "Ah, this is Japan!" kind of feeling. Did you know that Bruno Taut (the German architect stayed in Japan for three and a half years from 1933) liked using bamboo and shoji? Japanese designers were very disappointed by this and complained that even Taut was not able to go beyond the "Fujiyama, geisha" image.

That's right. I think it is the most important thing to do. I don't use shoji (paper screen) and bamboo because they evoke the "Ah, this is Japan!" kind of feeling. Did you know that Bruno Taut (the German architect stayed in Japan for three and a half years from 1933) liked using bamboo and shoji? Japanese designers were very disappointed by this and complained that even Taut was not able to go beyond the "Fujiyama, geisha" image.

―― I suppose you want to break stereotypes like "Fujiyama, geisha."

Fujimori:

I have a feeling that Kengo Kuma thinks the same way. That's probably why he uses wood in modern ways.

I have a feeling that Kengo Kuma thinks the same way. That's probably why he uses wood in modern ways.

―― Another idea would be to show visitors from overseas the essence and beauty of traditional Japanese architecture.

Fujimori:

I don't think so. Instead of architecture, I want them to see omotenashi (Japanese hospitality) offered in the tea house. Many people in different parts of the world take an interest in Japanese tea houses, but similar building types do not exist in other cultures. This way of formally entertaining guests in such a confined space is unique to Japan. I want people to experience that.

I don't think so. Instead of architecture, I want them to see omotenashi (Japanese hospitality) offered in the tea house. Many people in different parts of the world take an interest in Japanese tea houses, but similar building types do not exist in other cultures. This way of formally entertaining guests in such a confined space is unique to Japan. I want people to experience that.

―― It will disappear after the exhibition period is over.

Fujimori:

Yes, that's exactly why I hope it will remain in people's memories.

Yes, that's exactly why I hope it will remain in people's memories.

(Interview conducted and written by Wakato Onishi, Editorial Board Member, Asahi Shimbun)

In Part 2, Terunobu Fujimori will compare the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics and talk about how the city, architecture, and people of Tokyo have changed, in addition to his expectations for Tokyo's future.

Archives

The first interview features architectural historian and architect Terunobu Fujimori (Professor Emeritus at the University of Tokyo.) He shared his ideas about the pavilion with us in addition to some of the sketches of his design.

After discussing his pavilion in Part 1, Terunobu Fujimori talked about how the city, architecture, and people of Tokyo have changed, in addition to his expectations for Tokyo's future in relation to the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics in Part 2.